Chips and Missing Pieces of Tombs at the Museum of Fine Arts

| KV46 | |

|---|---|

| Burying site of Yuya and Thuya | |

| KV46 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′27″N 32°36′10″Due east / 25.74083°N 32.60278°E / 25.74083; 32.60278 Coordinates: 25°44′27″N 32°36′10″E / 25.74083°N 32.60278°Due east / 25.74083; 32.60278 |

| Location | E Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 5 Feb 1905 |

| Excavated by | James E. Quibell |

| ←Previous Side by side → | |

Tomb KV46 in the Valley of the Kings is the tomb of the ancient Egyptian noble Yuya and his wife Thuya, the parents of Queen Tiye and Anen. It was discovered in Feb 1905 by Chief Inspector of Antiquities James E. Quibell, excavating under the sponsorship of American millionaire Theodore M. Davis. Despite robberies in artifact, the undecorated tomb preserved a cracking deal of its original contents including chests, beds, chairs, a chariot, and numerous storage jars. Additionally, the riffled but undamaged mummies of Yuya and Thuya were found within their disturbed coffin sets. Prior to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, this was considered to exist one of the greatest discoveries in Egyptology.[i]

Layout [edit]

KV46 consists of a xv-step staircase leading to a descending corridor, a further set of short stairs, a second corridor with stairs and niches, and a rectangular burying chamber, the western third of which is 1 metre (3.iii ft) deeper than the rest of the flooring.[two] [1] The walls of the tomb are not decorated and were not smoothed, maybe due to the poor quality of the limestone; the only markings on the walls are black dots 40 centimetres (16 in) apart on the smoother walls;[2] they may be mason's marks.[i]

Location and discovery [edit]

KV46 was discovered on five February 1905 in excavations undertaken by James Quibell, on behalf of Theodore Davis. The tomb is located in a side valley between KV3 and KV4.[3] [4] Davis' previous 1902–1903 digging season had discovered the tombs of Thutmose 4 (KV43) and Hatshepsut (KV20) in a modest side valley and excavations resumed in this area on 17 December 1904.[2] Finding that nothing had been uncovered upon his arrival in Jan 1905, excavations shifted to a narrow, equally-yet unexplored area between the tombs KV3 and KV4.[5] This area was covered by a "great bank of chips, evidently artificial, and evidently untouched for a adept long while" which Quibell thought might conceal an before tomb.[four] Characterising the location as "most unpromising",[5] Davis states in his publication that "adept exploration justified its excavation, and that it would be a satisfaction to know the entire valley, even if it yielded nothing."[5]

Excavation commenced on 25 January 1905 and on vi February Davis was shown the starting time step of the tomb cutting past his excited foreman and workers; by the evening of 12 February the door was completely exposed. The door and busy lintel were cut into the solid stone and measured 4.02 past 1.35 metres (13.two ft × 4.4 ft). The doorway was blocked past stones cemented with mud plaster but was open up for the summit eighteen inches (46 cm), indicating that the tomb had been opened and probably robbed in antiquity. Despite it being nearly dark, Davis and Arthur Weigall, the new Chief Inspector of Antiquities, peered through the gap in the blocking. They saw a steeply declining corridor and Davis spotted a cane lying close to the door.[vi] Lacking a ladder, a small boy, the son of the reis (foreman),[7] was lifted in to call up the item; he returned with a gilt stone scarab and the yoke of a chariot in add-on to the pikestaff. That evening, Davis showed these items to Gaston Maspero who, intrigued both past the items and the identity of the tomb'southward owner, asked to be nowadays at the entry into the tomb the next solar day.[6]

Investigation [edit]

An Egyptian excavator beside the outer mummiform coffin of Yuya

On the morning of xiii February the blocking was carefully dismantled and Davis, Maspero, and Weigall entered the tomb. The group used candles for illumination as, although electricity was installed at the doorway, electricians were not present to extend it into the tomb.[8] Quibell was not in omnipresence every bit he was at Edfu acting as the official guide of the Duke of Connaught.[9] [ii] After descending downwards the steep corridor, a blocked and plastered doorway stamped with seals was encountered; this too had been breached at the top in antiquity. On either side of the doorway were pottery bowls containing the remains of the mud plaster used to seal the blocking. Catching glimpses of gold glittering in the candlelight, the trio took down the top course of the blocking and entered the burial chamber. Davis describes the first moments:

The bedroom was as dark as dark tin can be and extremely hot... We held up our candles, simply they gave then little light and and then dazzled our optics that we could see nothing except the glitter of gold.[8]

Looking to identify the owner of the tomb, they inspected a large wooden bury on which Maspero read the name 'Yuya'; Davis recounts that, in his own excitement, he almost touched the candles to the black resin surface. Realising how shut they had come to a possible peppery death, they made a hurried leave and returned afterward with electric lights. The space was revealed to be filled with a jumble of objects including sarcophagi, gilt and silvered coffin sets, canopic chests, a chariot, beds, chairs and other items of furniture, and various vessels. The riffled simply intact mummies of Yuya and Thuya were withal lying in their coffins.[10]

The hazard of robbery was felt to exist very real despite the presence of guards, then the contents were planned, recorded, photographed, and packed for ship to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo as quickly every bit possible. On 3 March the entire contents of the tomb had reached the river; they were loaded onto a train the next day and arrived under armed guard to the museum.[2]

During the clearance of the tomb, the excavators received a visit from a adult female who, unknown to them, was Empress Eugenie of France. Still, Quibell looked to entertain his guests, and apologised for the fact that most of the contents had been packed away for aircraft to Cairo. Joseph Lindon Smith, who assisted with the excavation recalls the following exchange:

The woman replied, "Practice tell me something of the discovery of the tomb."

Quibell said, "With pleasure, merely I regret that I cannot offer you a chair."

Quickly came her answer. "Why, there is a chair which volition practice for me nicely." And before our horrified optics she stepped down onto the floor of the chamber and seated herself in a chair that had not been sat in for over three g years![xi]

The chair in question was the throne of Princess Sitamun; surprisingly its strung seat held up the unexpected guest, as the 2 men were too embarrassed to tell her to get up.[9]

Contents [edit]

Program of the contents of KV46 from Quibell's 1908 publication

Until the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, this was the richest and best preserved tomb found in the valley, and the first to be establish with major items in situ.[1] The many objects crammed into the bedchamber led Weigall to liken the tomb to re-entering a house after a menstruum of disuse:

Imagine entering a boondocks business firm which had been airtight for the summer: imagine the stuffy room, the stiff, silent appearance of the piece of furniture... That was possibly the get-go sensation as nosotros stood, really dumbfounded, and stared effectually at the relics of the life of over three thousand years ago, all of which was as new most as when they graced the palace...[12]

Domestic furniture was readily apparent, every bit to the left of the doorway saturday the largest of the three chairs in the tomb. The wooden chair, known as the chair or throne of Sitamun, is veneered with a ruby-red wood and features aureate decoration; the back rest has a doubled scene of the seated Sitamun, their granddaughter, receiving a collar from a servant. The chair is of suitable size for an adult. To the right stood another chair, the smallest, known every bit the 'ibex chair' equally its artillery have an open-work design of a kneeling ibex. The 3rd chair likewise pocket-sized and is entirely golden. The back rest features Queen Tiye, seated, with a large cat under her chair, accompanied by Sitamun, and some other daughter on a papyrus boat. The chair was likely for a child and wear to the gilding suggests it was well used before beingness placed into the tomb.[13] [14]

The large wooden sarcophagi and coffin sets of Yuya and Thuya occupied most of the space in the tomb, with Yuya'south confronting the northern wall and Thuya'southward against the southern; both sarcophagi faced w. Their large size meant they must have been assembled and mayhap finished in the tomb, every bit there are no breaks in the gilt decoration. One finish of Yuya'southward sarcophagus had been broken in and the lid displaced; the lids of his 3 nested coffins had been removed, with 2 laid on top of each other partially supported by the chair of Princess Sitamun and the tertiary on its side against the coffins. His gilt cartonnage mask was broken and his mummy had been investigated by robbers, as the trunk lay in the remnants of its torn wrappings. Thuya'south sarcophagus had been partially dismantled, with the lid placed on one of the two beds and ane side placed on top of it, and the southern side had been placed against the wall. This immune her two nested coffins to be removed; the lid of the outer 1 had been thrown atop 1 of the beds while the trough had been thrown into the far corner of the tomb. The inner bury even so had its chapeau on.[2]

The canopic chests were placed close to the sarcophagi of their corresponding owners and were as well facing west. The two boxes are very similar, having sloping roofs and gilded plaster decoration on black backgrounds. The lids of both boxes had been moved but the alabaster canopic jars and embalmed viscera, which in the instance of Thuya were shaped like mummies and wearing gilt masks, were undisturbed. Under the beds and in the corner by the door were caskets and boxes, while inside or under the upturned bury lids and troughs were diverse items including cushions, a wig, alabaster vases, and lids of caskets. The chests and boxes contained items such as sandals, model tools for ushabti, cloth, and the lids of ushabti boxes.[2]

A total of nineteen ushabti were present in the tomb - xv inscribed for Yuya and four for Thuya. Most of the ushabti were still in their boxes, placed betwixt Yuya's sarcophagus and the wall; a further 4 were recovered from a box by the doorway. The majority of the figures are made of wood, several of cedar and one of ebony, often with gilded faces and wigs or collars.[fifteen] Two of Thuya's ushabti are covered with silvery leaf and ii are aureate.[16] An unusual example is made of copper sheet over a wooden core. The figures are inscribed with Spell vi of the Book of the Expressionless, instructing them to practise the work of the deceased in the realm of the dead; Yuya's alabaster ushabti is uninscribed. Seven of Yuya's ushabti were stolen from the Egyptian Museum during the 2011 Egyptian revolution; half dozen have since been recovered.[fifteen]

The western 3rd of the room with the lower floor was filled with l-two large vessels containing natron; to a higher place the pots was a bed, a large reed mat, a wig basket, the cartonnage mummy bands of Thuya, and 18 boxes of dried foods.[2] Likewise placed in this area was the chariot of Yuya, found to be in a virtually perfect state of preservation.[17] The thin wooden body, which curves to encounter the handrail at the centre and sides, features a raised design in gilded plaster of a tree of life flanked by two browsing goats, standing upright. The rest is filled by rosettes and spirals, with a design of a combined lotus-tree of life to a higher place the axles. The interior of the torso paneling is painted green. The sides of the chariot were filled by panels of red leather with green applique borders; these panels had been ripped away by tomb robbers. A similar console remains in place at the dorsum of the chariot. The floor is D-shaped and constructed of a woven leather mesh covered past a piece of red leather. The torso is supported by the pole and axletree. The wheels take six spokes and are secured to the axle with leather pegs; the projecting outer end of the axle is covered with argent foil. The wheels have red leather tyres which bear witness very little wear, leading to suggestions that information technology was used only for the funeral procession. The pole is approximately 2 metres (6.six ft) long and decorated with three bands of gold foil and capped with silver foil. It was fitted with a wooden yoke, made from a single piece of wood, which was pegged and tied into identify with dark-green leather lashing. The yoke too features decorative gilt bands. Quibell suggests the chariot was too low to be used by horses and that the gilded decoration made it unsuitable for practical use.[17] [18]

Another remarkable discover was Yuya's copy of the Book of the Expressionless, measuring 9.vii metres (32 ft) and containing forty capacity, many of which were illustrated with vignettes. In his publication, Edouard Naville characterises it every bit a "good specimen of a Book of the Dead of the XVIIIth Dynasty."[19] Information technology was written in cursive hieroglyphs, as was typical for the era. The chapters were prepared beforehand, with spaces left for the insertion of the owner's name and titles. Later, a second scribe with slightly different handwriting added the names, adapting to the bachelor infinite which resulted in longer, shorter, or entirely absent titles. Some of the capacity are abbreviated, with those accompanied by vignettes oft the almost shortened due to insufficient space being allowed for the text. The papyrus begins with a scene of Yuya and Thuya doting Osiris. Here, and again in a later chapter, Yuya is depicted with white pilus, possibly as a sign of old age. The get-go chapter is accompanied by a vignette of the funeral procession, with the mummy arriving at the tomb on a sledge pulled by men and cattle. Other chapters present include those which allow the deceased to accept the forms of diverse animals, to defeat their enemies, prescriptions for ideal funerary amulets, and the weighing of the heart. The final affiliate is followed by two lines declaring the text to be "drawn, checked, examined, weighed from part to part", an balls from the writer that the preceeding work is reliable.[20]

In his publication of the tomb, Davis claims he declined Maspero'south offer of a share of the tomb's contents, citing that it "ought to be exhibited intact."[10] Even so, Quibell's after catalog notes that 3 wooden ushabti were in Davis' possession;[21] he later ancestral three shabti, 2 shabti boxes, model tools for shabti, a pair of sandals, and two sealed storage jars from the tomb to the Metropolitan Museum in 1915.[22]

Robberies [edit]

KV46 was robbed in artifact, nigh probably three times: a first time shortly later the closure of the tomb, and then twice during the construction of the next tombs KV3 and KV4. During the first looting, only perishable products such every bit oil were removed; those that had gone rancid were left. The 2nd and third times however the looters took most of the jewellery and linen not directly associated with the mummies. A small-scale effort was fabricated to restore club to the tomb later the robberies, with Thuya's trunk covered by a shroud, boxes refilled, and the breached blocking partially re-stacked.[ane]

Mummies [edit]

The well preserved mummified bodies of Yuya and Thuya were establish yet in their coffins, although both had been disturbed by robbers. Davis was particularly struck by Thuya, who was lying covered in fine cloth, with only her caput and anxiety exposed.[ten]

I had occasion to sit by her in the tomb for well-nigh an hour, and having nothing else to see or do, I studied her confront and indulged in speculations germane to the situation, until her dignity and character so impressed me that I almost establish it necessary to apologize for my presence.[ten]

The Australian anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith was the first to examine the bodies for Quibell's 1908 publication of the tomb in which he characterizes them both equally perfect examples of the embalmer's art.[23]

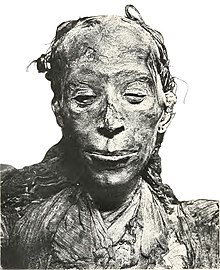

Yuya [edit]

The mummy of Yuya was establish yet partially wrapped, with only his torso being divested of wrappings past ancient robbers. Despite this disturbance, the thieves had missed the gold plate (113 by 42 millimetres (iv.iv in × one.7 in)) covering the embalming incision.[23] When the body of Yuya was removed from his innermost coffin, a partially strung necklace composed of big gold and lapis lazuli beads was found backside his neck, where it had presumably fallen afterwards being snapped by robbers.[10] The intact wrappings covering the caput were removed before the body was shipped to Cairo.[23]

The body of Yuya is that of an erstwhile human being, one.651 metres (5.42 ft) alpine, with white wavy pilus now discoloured by the embalming process; his eyebrows and eyelashes are dark brownish. The arms are bent with his hands placed under his chin. A gold finger stall was establish on the little finger of the correct mitt. There were linen embalming packs placed in front of the eyes, and the torso cavity was stuffed with resin-treated linen packs. Smith guessed his age at death to be lx based on outward appearance alone.[23] Modern CT scanning has estimated his age at death to be fifty to sixty years, based on the level of articulation degeneration and tooth clothing; his cause of expiry could non exist identified.[24] Maspero judged that, based on the position of the sarcophagi, Yuya was the first to die and be interred in the tomb.[25] Withal, the big eyes and pocket-size olfactory organ and oral fissure seen on his funerary mask suggests it was fabricated during the final decade of the reign of Amenhotep III, meaning he may have outlived Thuya.[26]

While Smith notes that his features are not classically Egyptian, he considers that there was much migration from neighbouring countries throughout Egyptian history and "it would be rash to offering a concluding stance on the subject of [Yuya'south] nationality."[23]

Thuya [edit]

The wrappings of Thuya were more disturbed than those of Yuya. She was covered with a large linen shroud knotted at the back and secured by iv bandages. These bands were covered with resin and opposite each band was the golden titles of Thuya cut out of gold foil. The resin coating on the lower layers of bandages preserved the impression of a large broad collar.[23]

The body of Thuya is that of an elderly woman of modest stature, one.495 metres (4.90 ft) in height, with white hair. Her arms are direct with the hands confronting the outside of her thighs. Her embalming incision is stitched with thread, to which a carnelian barrel dewdrop is attached at the lower end; her body cavity is stuffed with resin-soaked linen. When Dr. Douglas Derry, (who later conducted the first examination of Tutankhamun's mummy) assisting Smith in his examination, exposed Thuya'due south feet to become an accurate measurement of her meridian, he institute her to be wearing gold foil sandals. Smith estimated her historic period at more fifty years based on her outward advent solitary.[23] Contempo CT scanning has estimated her historic period at death to exist l to 60 years quondam. The scan also revealed that she had severe scoliosis with a Cobb bending of 25 degrees. No cause of death could be determined.[27]

Objects found in KV46 [edit]

-

Mummy mask of Thuya

-

Mummy mask of Yuya

-

2d and inner coffins of Yuya

-

Thuya's third bury

-

Mummified entrail of Thuya with cartonnage mask

-

Blue enamelled and gilt coffer bearing the Horus proper name, prenomen and nomen of Amenhotep 3

-

Gilded head to bedstead representing the god Bes

-

The gilded 'ibex' chair

-

A gold chair, the dorsum depicts a canoeing scene

-

Sealed storage jar, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of sandals, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Shabti and shabti boxes of Yuya, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Food storage jar, now in the Oriental Institute Museum, Academy of Chicago

-

Vignette of Yuya from his Volume of the Dead

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 174-178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Quibell & Smith 1908, p. I-VII.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 174.

- ^ a b Quibell & Smith 1908, p. I.

- ^ a b c Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. XXV.

- ^ a b Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. XXV--XXVII.

- ^ Romer 1981, p. 199.

- ^ a b Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. XXVIII.

- ^ a b Romer 1981, p. 197-204.

- ^ a b c d due east Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. XXV-Thirty.

- ^ Smith 1956, p. 41-42.

- ^ Weigall 1911, p. 174-175.

- ^ Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. 37-44.

- ^ Quibell & Smith 1908, p. 52-54.

- ^ a b Mekawy Ouda 2021, p. 21-xl.

- ^ Quibell & Smith 1908, p. 38-39.

- ^ a b Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. 35-36.

- ^ Quibell & Smith 1908, p. 65-67.

- ^ Quibell & Smith 1908, p. 73.

- ^ Hayes 1959, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d east f chiliad Quibell & Smith 1908, p. 68-73.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 68-71.

- ^ Davis, Maspero & Newberry 1907, p. XXI.

- ^ Forbes 1996, p. 40-45.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 71-74.

Bibliography [edit]

- Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, G.; Newberry, Percy Due east. (1907). The Tomb of Iouiya and Touiyou. London: Archibald Constable and Co. ISBN0-7156-2963-8.

- Forbes, Dennis (1996). "KMT Photo-Exclusive: Yuya's Mummy-Mask Debuts in Cairo After 91 Years". KMT: A Modern Periodical of Ancient Egypt. 7 (two): 40–45.

- Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar Due north. (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. Cairo: The American Academy in Cairo Press. ISBN978-977-416-673-0.

- Hayes, William C. (1959). The Scepter of Arab republic of egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. Two The Hyksos Period and the New Kingdom (1675–1080 B.C.) (1990 (revised) ed.). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Mekawy Ouda, Ahmed Chiliad. (June 2021). "The Shabtis of the God's Father, Yuya". The Periodical of Egyptian Archaeology. 107 (ane–two): 21–twoscore. doi:10.1177/03075133211059842. ISSN 0307-5133. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Naville, Edouard (1908). The Funeral Papyrus of Iouiya. London: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- Quibell, J. E.; Smith, Grafton Elliot (1908). Tomb of Yuaa and Thuiu. Le Caire Impremerie De L'Institut Francais D'Archeologie Orientale.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Arab republic of egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-28403-2.

- Romer, John (1981). Valley of the Kings. London: Book Club Associates.

- Smith, Joseph Lindon (1956). Smith, Corinna Lindon (ed.). Tombs, Temples & Ancient Art. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Weigall, Arthur Due east. P. B. (1911). The Treasury of Ancient Egypt. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 178–182. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to KV46. |

- Theban Mapping Project: KV46 - Includes detailed map of the tomb.

pomeroyyoultaid54.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Yuya_and_Thuya

0 Response to "Chips and Missing Pieces of Tombs at the Museum of Fine Arts"

Post a Comment